The term ‘genre’ in English is a recent import from French. We can see that it is a recent borrowing because the initial ‘g’ is pronounced ‘zh’ like French. Compare this with the older word ‘gender’, where the initial ‘g’ is pronounced ‘dzh’ like other similar English words (‘gesture,’ ‘gin’, and ‘judge’ for example). The ‘d’ is introduced to make the word easier to pronounce in English, similar to the ‘d’ on the end of ‘sound’ compared with French ‘son’.

‘Genre’ and ‘gender’ are in fact the same word, imported from French into English at different times, ‘genre’ more recently.

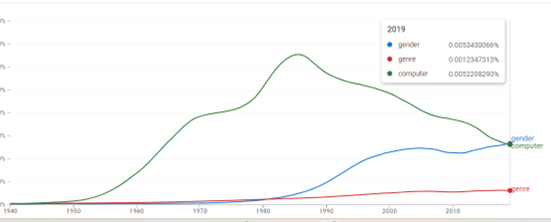

Both are very modern terms. The frequency of use of the words shows that, in writing at least, they only started to became popular in the 1960s and 1970s, with a particular surge in the use of the term ‘gender’ in recent years. According to Google N-gram, the frequency of use of the word ‘gender’ was, in 2019, equal to that of the word ‘computer’.

Figure 1: Frequency of use of terms ‘gender’ and ‘genre’ according to Google N-gram, 1600-2019 https://books.google.com/ngrams/graph?content=gender%2Cgenre&year_start=1600&year_end=2019&corpus=en-2019&smoothing=3

Figure 2: Frequency of Use of words ‘gender’ and ‘genre’ compared with ‘computer’, 1960 to 2019. https://books.google.com/ngrams/graph?content=gender%2Cgenre%2Ccomputer&year_start=1940&year_end=2019&corpus=en-2019&smoothing=3

Historically ‘genre’ tends to have negative connotations. ‘Genre’ paintings depict scenes from everyday life (often in a stereotypical fashion) and are aimed at a middle-class/bourgeois audience. They are contrasted with the historical paintings and portraits preferred by the aristocracy. Vermeer is an early example of ‘genre painting’ before the term attracted negative connotations.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Genre_painting

Vermeer: “Lady Writing a Letter with her Maid” 1670/1.

In filmmaking, ‘genre’ movies have often been considered low status, compared to ‘drama’. They rarely win Academy Awards. Hitchcock, for example, was not regarded as a great director during his lifetime because he made ‘thrillers’. Great directors, such as Stanley Kubrick, have tended to work in a variety of genres or develop their own unique style.

The term ‘genre’ in French, which is the origin of both ‘gender’ and ‘genre’ in English originally means simply ‘kind’ or ‘type’. It is related to the Latin word ‘gens’, meaning ‘people’ or ‘extended family’. ‘Gene’, ‘genetics’, ‘genealogy,’ ‘general’ and the Portuguese word ‘gente’, which is used as an indefinite 2nd and 3rd person plural, similar to ‘on’ in French, all come from the same Latin root.

Neo-Latin languages tend to have two genders, described as ‘masculine’ and ‘feminine’, while Latin itself and other Indo-European languages, such as German and Ancient Greek, have three — ‘masculine’ ‘feminine’ and ‘neuter’. Some non-Indo-European languages, such as Hebrew, also have gender. Many languages, however, have no gender—English being the prime example.

Linguistic gender is, in fact, a subset of a larger concept called ‘class’. In many African languages, for example, nouns are divided fairly arbitrarily into many different classes (which may or may not be related to biology). The Aboriginal language Dyirbal famously has a class of nouns that includes ‘women, water, fire, and dangerous things’!

A similar phenomenon can be found in some Asian languages (such as Japanese and Chinese), which use different ‘counters’ or ‘measure words’ for different classes of noun (again fairly arbitrarily). Chinese for example has a special word that is used to count ‘long thin things’ – ‘noodles, ‘sticks’, ‘fingers’, ‘tails’, ‘legs,’ ‘jeans’ and so forth.

This phenomenon is minimally present in English. The word ‘loaf’, for example, is only used to count ‘bread’. ‘Two loaves of bread’. Collective nouns such as ‘flock’ or ‘herd’ are only used for specific types of thing. ‘Flock’ for example can be used for any kind of bird–‘a flock of seagulls’ ‘a flock of geese’. With mammals, however, the word can only be used with ‘sheep’: ‘a flock of sheep’, but a ‘herd of cows’, a ‘herd of elephants’, a ‘herd of goats’. By extension, ‘flock’ can be used for a group of people or things that resemble birds or sheep: ‘a flock of tourists’, ‘a flock of clouds’, for example. ‘Flock’ is sometimes also used, somewhat pejoratively as a verb: ‘Young people flocked to the theaters to see the latest Bond movie.’

The term ‘gender’ was thus originally unconnected to biology, meaning only a type or a kind. In the late 19th and early 20th century, the more common technical term (‘sex’) began to take on erotic connotations and the term ‘gender’ became preferable. ‘Sex,’ however, persisted in academic publications until the 1980s, when it came to be replaced by ‘gender’. Sociologists and feminists, from the 1960s and 70s onwards were also coming to use the term ‘gender’ for a sexual identity that is socially constructed rather than biological. This is an ongoing controversy.

Interestingly, the term ‘gender bender’ to refer to transsexualism was first used in 1977 to refer to David Bowie.

For more information on the etymology of these words, see https://www.etymonline.com/word/genre

https://www.etymonline.com/word/gender

For a more academic discussion on the use of the terms ‘gender’ and ‘sex’ in scientific writing, see this article from the Journal of Applied Physiology https://journals.physiology.org/doi/full/10.1152/japplphysiol.00376.2005#:~:text=In%20the%20journals%20of%20the,of%20sex%20(Table%201).

For the linguistic concepts of gender, class, and measure words, see the following:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Grammatical_gender

Very interesting!

[…] Gender and Genre […]